The article was first published on www.syrianska.net.

During the dark years of World War I, one of history’s most horrifying tragedies unfolded—the systematic genocide of Syriac Christians in the Ottoman Empire. This event, known as “Seyfo” (the sword) in Syriac, was a brutal crime against humanity in which hundreds of thousands of people were murdered or forced to flee for their lives. One of the few who documented these horrific events was the Swedish missionary Alma Johansson, whose accounts and correspondence offer a personal and poignant insight into the suffering and barbarity.

Alma Johansson’s Role as a Witness

Born in Sweden in 1880, Alma Johansson traveled to Anatolia in the early 1900s as part of the Swedish Missionary Society. She settled in the city of Mardin, where she worked to support women and children within the Syriac Christian population. Her mission was initially to provide aid and education to the most vulnerable, but when the genocide broke out in 1915, she found herself in the midst of chaos and became an eyewitness to the horrors committed against the Syriac Christians.

Her letters home to Sweden and later testimonies are shocking documentation of how the abuses escalated from discrimination to systematic extermination. Through her words, we not only gain an understanding of the political and social forces that drove the genocide, but also a deep sense of the individual suffering and courage of the victims.

Accounts of Violence

Alma Johansson’s reports from 1915 provide a detailed and heartbreaking description of how the massacres were carried out. In one of her letters, she writes:

“I saw the bodies of men piled up at the city gates, like a warning to all who dared defy orders. Women and children were forced to march in long lines away from their homes, without food, without water, without any idea where they were going. I have never seen anything like it. This is not war; this is pure hatred.”

She describes how villages were attacked by armed groups, often local militias acting under the orders of Ottoman authorities. Men were taken from their families and murdered on the spot, while women and children were deported under horrific conditions. Those who did not die from hunger, thirst, or exhaustion were murdered along the way, and many were forced to convert to Islam to survive.

One of the most harrowing examples in Alma’s accounts concerns the women of Mardin. She writes:

“I have seen women choose to throw themselves off cliffs rather than become slaves. I have seen girls raped and then left to die in the desert. Every day brings new stories of suffering that I can barely carry. But I must go on, because who else will tell their story?”

In another letter, she describes the fate of the deported women:

“Those who do not die during the march are sold as slaves in the markets. I have seen young girls torn from their mothers and disappear forever. I have seen elderly women kicked and beaten because they couldn’t keep up. This is not an act of war; this is evil in its purest form.”

The Political Context

The Syriac genocide was not spontaneous violence but part of a broader strategy to “cleanse” the Ottoman Empire of non-Muslim groups. The Ottoman leaders, driven by nationalist ideals and Turkish supremacy, viewed Syriac Christians as a threat to their vision of a unified empire. Propaganda portrayed these groups as enemies of the state and allies of the European powers, which served to justify their extermination.

Alma Johansson quickly realized that this was not just a local conflict but an organized campaign. She reported how Ottoman soldiers and local authorities collaborated in carrying out deportations and massacres. Despite being a foreigner and a missionary, she was treated little better than the victims; she lived under constant threat and experienced how her work was sabotaged and endangered.

Consequences and Legacy

When the genocide was over, thousands of people had lost their lives, and the survivors were forced to live in exile. Alma Johansson remained in the region for as long as she could, but when the situation became unbearable, she returned to Sweden. There, she continued to write about her experiences and worked to raise awareness of what had happened.

Her books, such as In the Land of the Moors (1907) and My Life Among Oppressed Women (1924), are important historical documents that have contributed to our understanding of the genocide of the Syriac Christians. Through her words, we come to understand not only the macabre details of the massacres but also the human stories behind the statistics.

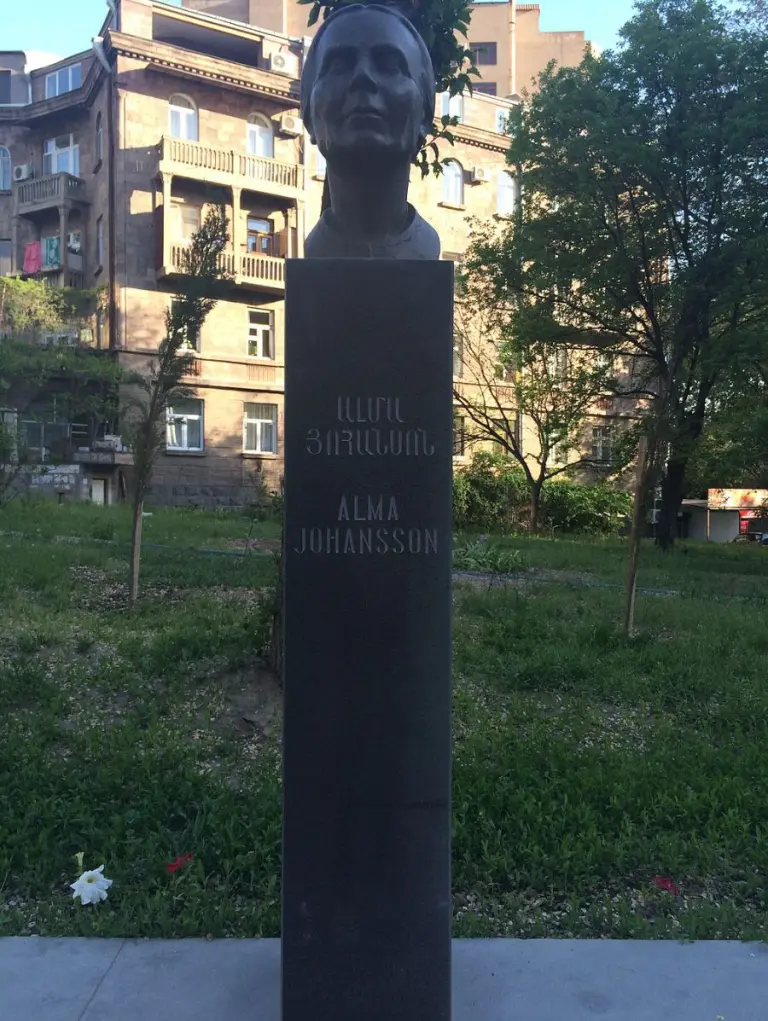

Remembering Alma Johansson’s Legacy

Today, the memory of the Syriac genocide lives on thanks to people like Alma Johansson, whose courage and empathy made her a voice for those who could no longer speak. Her documentation of the events serves as a reminder of the importance of bearing witness to injustice and striving for truth and justice.

By reading and reflecting on Alma’s stories, we see how vital it is to acknowledge and remember genocide. History teaches us that hatred and intolerance must never prevail, and that we all have a responsibility to stand up for the most vulnerable in our society. Alma Johansson’s life and work are a powerful example of how the actions of a single individual can make a difference—not only for those suffering in the present, but also for future generations seeking understanding and reconciliation.

By Abraham Tekin